Small Farm Success Factors

How do you know which small farm success factors are important to YOUR operation?

How do you know which small farm success factors are important to YOUR operation?There are a lot of factors that contribute to the success of a small farm. When you dig into the topic a little, you might see advice that suggests effective planning is key, or the use of cover crops and crop rotation, or good marketing and community relations.

Or any of a dozen other ‘techniques’ that turn up when you do a little research.

This can be confusing; how do you action all these ideas to improve profitability on your small farm? To my mind, all these small farm success factors boil down to two things:

1. Managing costs;

2. Managing production.

But here’s the rub: you can’t manage anything until you understand it. And you can’t understand it unless you measure it.

“Data!data!data!"

he cried impatiently. "I can't make bricks without clay.”

From Sherlock Holmes, The Adventure of the Copper Beeches in case you didn’t get the quote. In my ‘other life’ I was a performance measurement expert; Conan-Doyle would have made a great partner.

So what data are we talking about? You need data drilled down to a sufficiently granular level to support informed decision making about your methods, your crops and your priorities.

That’s a mouthful, so here’s an example:

For the first couple years in the New Terra Farm market garden we rototilled and then shaped raised beds by hand.

My tracking showed it took two farm helpers about 15 minutes to rake up and prepare a 50-foot bed. Since they were being paid $10/hour, the cost to shape each bed was about $5.00 (1/2 an hour at $10/hour).

And this activity was always a bottleneck in farm production; bed shaping by hand was hard work and the crew could only do so many beds a day.

So, we looked at options. A farming neighbour with bed-shaping equipment on his tractor could do my whole garden for $450. Since I had around 200 beds, this came to a per-bed cost of $2.25, less than half the 'manual' method.

Plus, all the beds were ready, so no more bottleneck in planting. The farm helpers were much happier doing less-strenuous, more productive tasks.

And I could more efficiently plan and place crops according to care needs e.g. I could group beds together that would be served by overhead irrigation or drip lines.

The overall savings in time and money and the increased efficiency from hiring a contractor were huge. This let us grow the garden bigger without putting a strain on our finances (or my back).

But I couldn’t make that decision without the costing data, drilled down to the individual bed level of costs.

Let’s expand on that idea a bit.

'Marketing and innovation produce results. All the rest are costs'.

That one is from Peter F. Drucker, in Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. My man Peter was a big time management guru/consultant.

He is also famous for saying ‘the purpose of a business is to create a customer’, hence the quote.

A lot of what he had to say about big business is surprisingly applicable to the small grower.

For example, he suggests one question the new manager needs to ask is ‘What is the minimum information I need to know I have control’?

So let’s take the next step in getting control of costs. Income statements and balance sheets are useful whole-farm measures of profitability, but control happens at the individual unit level e.g. you need to know the cost per pound, bushel, bed, row foot, or head for ALL the garden and livestock crops you offer for sale.

On the production side, you need to know the yield; i.e. how many marketable pounds, bunches, heads etc were harvested from that bed or row.

Now you are probably thinking ‘This seems like a LOT of work’. You are not wrong. But there is no other way to actually hold control over costs and production.

Here’s what I consider the minimum information you need.

The Ultimate Small Farm Success Factor – Detailed Record Keeping

Input Costs

- Seed

- Row cover

- Fertilizer

Labour

- Bed prep

- Fertilization & Irrigation set-up

- Planting

- Weeding

- Harvest Labour

- Wash and package

Marketable Yield

- # of Units produced per bed/row

To evaluate the profitability of a given crop you also need to know your expected price per unit.

Here’s a sample:

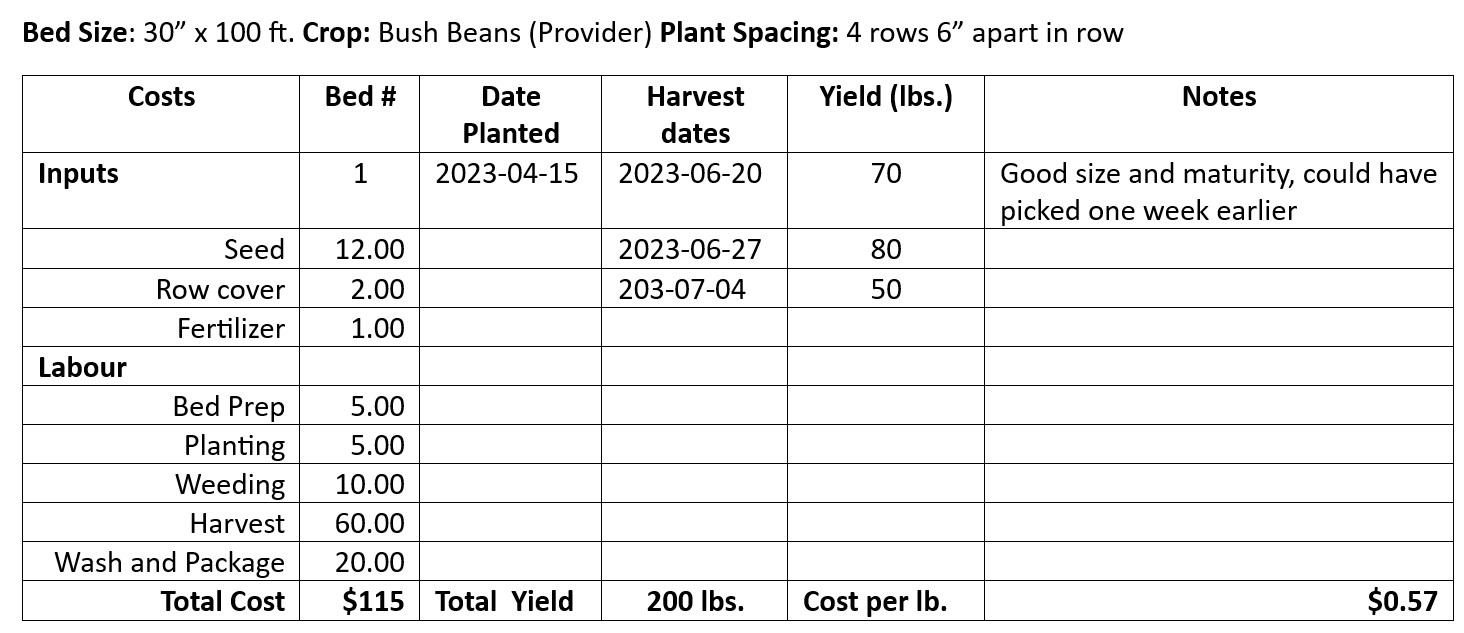

Sample log to track cost of inputs and labour

Sample log to track cost of inputs and labourIf you plan to sell your beans for $3/lb., you now know how much profit potential you have in this crop. Note this is a simple example that ignores overhead costs like amortization of farm equipment and the cost of the farmland itself.

For example, if your tractor cost $30,000 and you expect it to have a 10 year useful life, the cost of the tractor is $3,000 per year using straight-line depreciation (ignoring interest and salvage cost). If you have 200 garden beds, then the cost per garden bed is $3,000/200 = $15. in the example above, this would add $15/200 = $0.075 per pound of beans.

Let's talk a little more about the production side of small farm success factors.

'Production is not the application of tools to materials. It is the application of logic to work'.

Another gem from Peter Drucker. None of these small farm success factors will help unless you actually use this information to make decisions and decide where and on what you spend your (limited) time, attention and money.

Applying logic to work means you need to be able to answer some key questions.

Does crop A cost more to produce than crop B? Does crop A require more labor than crop B? Do I spend more on inputs producing crop A or crop B? Is it worthwhile to buy that neat piece of kit I saw at the farm show? Will it pay me back in reduced costs or increased production?

This applies to more than just purchases. Can I change my production methods to reduce labour costs – e.g. If I spend the time to ‘tarp’ a field, will the advantages of planting into a stale seed bed be worth the investment?

Can I quantify the benefits of cover cropping in enhanced soil (and plant) health and productivity?

I know for example, that my greenhouses have produced many thousands of dollars worth of transplants, and let me take advantage of early markets.

I know they have paid back their cost many times over because I kept track with a form a lot like the one above.

In that table you will also see that I am growing Provider green beans. My production records show that Provider can be planted earlier and produces more consistently than any other cultivar I’ve tried.

They continue to be my main crop for snap beans. I grow a couple other varieties each year as well, I keep looking for another winner.

If you are in the farming game for the long haul, being able to figure this stuff out is how you STAY in the game

In fact every intervention and investment you make on your small farm has to link back to reducing costs and/or improving production.

All that while not neglecting sustainability both economically and environmentally and personally.

You could reduce costs by firing all your farm help and working 18-hour days 7 days a week 365, but that is probably not a long-term win.

Much better to make sure that, if you are paying Joe Helper ‘X’, he is producing at least ‘2X’ in added value.

You figure that out the same way as shown above. If good old Joe can help you increase the area planted or let you add another profitable crop to the mix, he’s a keeper.

Mining out your soil health and nutrients is also not a long-term success strategy. Hence the practice of crop rotation, cover cropping and integrating livestock into your farm operation can be success factors.

My two ponies pay their way in the valuable manure produced that maintains fertility in my garden. I also rotate pigs and meat chickens through the garden areas. I buy some of their feed but at the same time I’m buying soil fertility.

Let’s wrap it up with one last quote.

Stephen Covey, ‘7 Habits of Highly Successful People’

All wonderfully good advice for ANY business

All wonderfully good advice for ANY businessA world of good advice here, but I want to focus on two success habits (and small farm success factors) here.

1. Be Proactive

2. Begin with the End In Mind

You need to think about and set up your record-keeping before you start dropping seeds in the ground. Decide how you are going to capture the information. Make sure all your field help knows this is part of the job.

While you are at it, make your accountant happy and set up your other record keeping was well. On my How to Start a Farm Page you will see my suggested starter list for records to keep.

For some further reading on farm finances and farm production check out this one from BeginningFarmers.org

And if you want a step-by-step guide to build a real plan for success on your small farm, check out my Bootstrap Boot Camp Success Plan course.

- Home

- Micro Farm Profit

- Small Farm Success Factors

Recent Articles

-

Backyard Garden Profits your key to a successful small market garden

Apr 06, 25 05:38 AM

I wrote Backyard Garden Profits for the small grower who wants to launch a successful side hustle gardening for money. Practical actionable advice small-scale growers who want to earn more, waste less… -

Homesteader Book Bundle only from New Terra Farm

Apr 01, 25 04:58 PM

If you have a hankerin' for country living, my best value Homesteader Book Bundle is a great resouirce. -

New Terra Farm market gardening book shows you success step-by-step

Apr 01, 25 04:33 PM

Start-up, market and manage a successful organic market garden with my Bootstrap Market Gardening Book